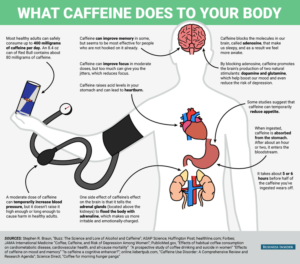

Soon after you eat or drink something containing caffeine, it is quickly absorbed through the small intestine and dissolved into the bloodstream. Caffeine is both water and fat soluble and is able to penetrate and be absorbed in the body and enter the brain. This produces the feeling of alertness that caffeine drinkers crave.

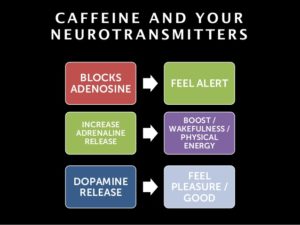

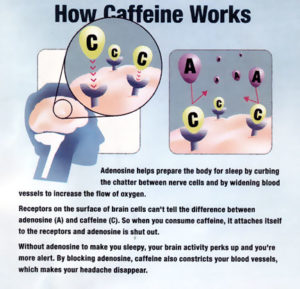

Structurally, caffeine closely resembles a molecule that’s naturally present in our brain, called adenosine (which is a byproduct of many cellular processes, including cellular respiration)—so much so, in fact, that caffeine can fit neatly into our brain cells’ receptors for adenosine, effectively blocking them off. Normally, the adenosine produced over time locks into these receptors and produces a feeling of tiredness.

Caffeine molecules block those receptors and prevent this from occurring, generating a sense of energy and alertness for a few hours. Some of the brain’s own natural stimulants (such as dopamine) work more effectively when the adenosine receptors are blocked. The surplus adenosine floating around in the brain cues the adrenal glands to secrete another stimulant called adrenaline.

The good news is that, compared to many drug addictions, the effects are relatively short-term. To kick the thing, you only need to get through about 7-12 days of symptoms without drinking any caffeine. During that period, your brain will naturally decrease the number of adenosine receptors on each cell, responding to the sudden lack of caffeine ingestion. If you can make it that long without a cup of joe or a spot of tea, the levels of adenosine receptors in your brain reset to their baseline levels, and your addiction will be broken.